Global food yields continue to grow. So does hunger

Global crop yields are growing despite climate change. Yet, wars and entrenched inequality are increasing global hunger.

Key points:

Our global agricultural system is working. It consistently produces more yield with less land, even with the effects of climate change.

Our global food system is not working. Global food insecurity is rising despite more food being produced per capita. Food insecurity and food production have become decoupled in the last decade.

Most of the hunger in today’s world is NOT caused by climate change (although it does not help). It is caused by conflict, inequality and Africa’s lack of access to modern agricultural technology.

Article

Different parts of the global food system are living in completely different universes. If you read the reports of national level agricultural departments, the story is that agricultural production continues to increase - even at a per capita level - despite pressure from climate change. This is true and a fantastic achievement.

If you read UN reports, the story is that 70 years of continual declines in food insecurity have begun to reverse in the last 5-10 years. The world will not meet its zero hunger goals. In fact the percentage and total number of people facing food insecurity is higher than five years ago. This is also true and a terrible outcome.

Farmers are producing more food - they have so far adapted well to climate change

Farmers around the world face changing environments. In Australia (my home country), temperatures have risen 1.4 degrees on average, winter rainfall has decreased, and seasonal variability has increased. This makes farming less predictable, and thus harder.

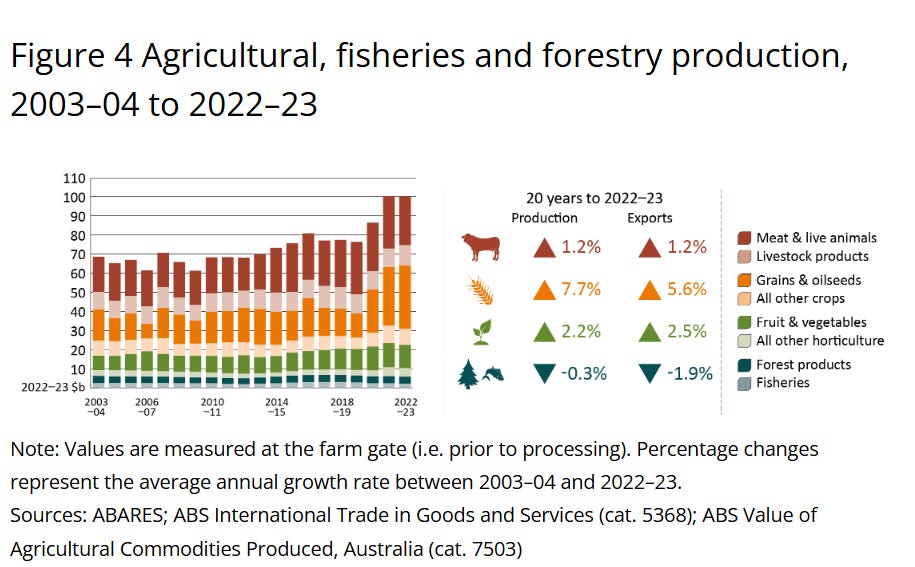

Yet, Australian farmers have consistently increased their output.

Source: Copied from Australian govt agriculture dept report

This is the ultimate climate change adaptation. Australian farmers are producing more food using less fertiliser, using less land while facing higher weather variability.

Increasing yields over the past twenty years (and the fifty years before that) have been the result of a range of incremental technology gains: better crop varieties, improved irrigation, better farm automation, better use of fertilisers, and improved weather forecasting among others.

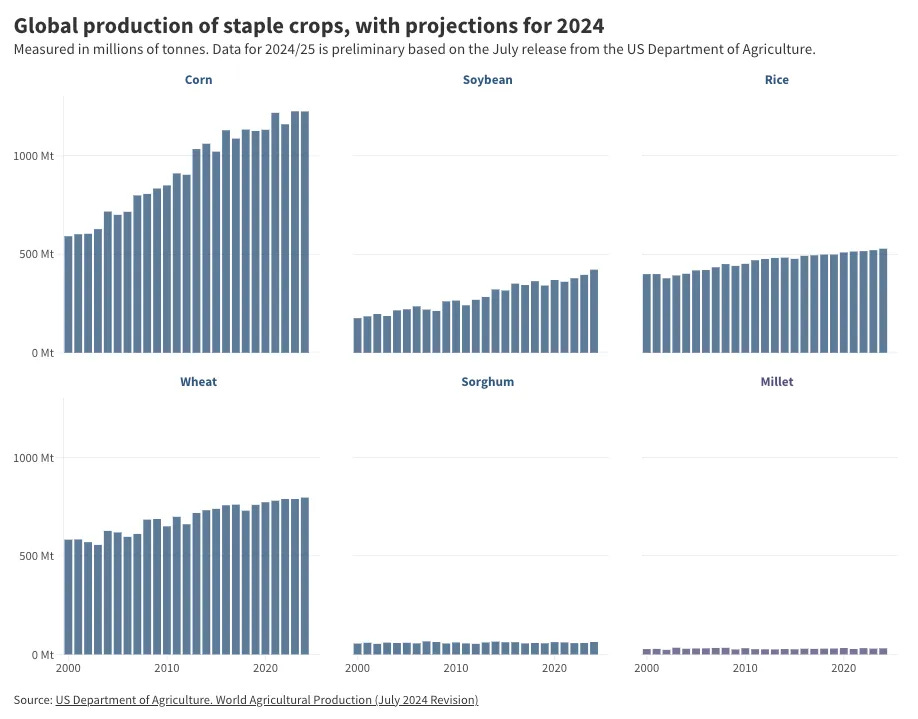

This trend has been repeated everywhere, with the exception of sub-Saharan Africa. The graph below from Hannah Ritchie shows the relentless increase of rice, soybean, corn and wheat yields. Sorghum and Millet - the staples of much of Africa - have not seen the same growth.

Source: Hannah Ritchie Substack, https://substack.com/home/post/p-146880793

Yet, more people are hungry

For 70 years, food insecurity improved hand-in-hand with better yields. Yet, in the last few years, hunger and food insecurity have worsened while food yields increase. Food yields have bizarrely decoupled from food insecurity.

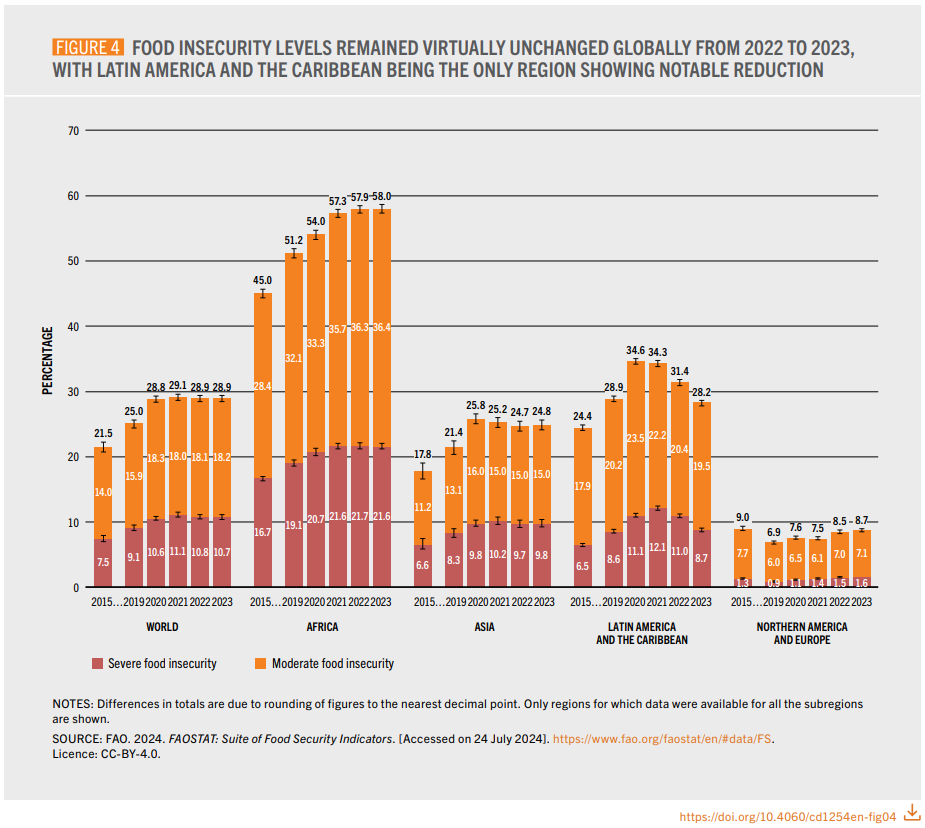

Below, you can see the percentage of people facing food insecurity - both severe and moderate - increased almost everywhere between 2015 and 2021. The rate of increase has levelled off in recent years. But in Africa and Asia, populations are still increasing so the total number of people facing food insecurity continues to increase (see page 15 of this FAO report).

Source: Copied From FAO Report: The State And Food Security And Nutrition In The World

To put this in a specific context, the number of undernourished people in the world dropped from 798 million in 2005 to 570 million in 2015 (page 8 of this report). This climbed back up to 733 million in 2023. One would be tempted to argue that the world’s population is growing, so it is not so bad. But the world’s population was also growing when the number of undernourished people was dropping. This tells us that our systems are not working as they once did.

Why the increase in hungry people?

Food systems are complex. But there seems to be three headline reasons this is happening.

Hunger increases for those in conflict zones

Nothing causes starvation like war. And there are a lot of global conflicts right now. Sudan, Gaza, Afghanistan, Yemen and Syria all sit near the top of global hunger lists.

There is one caveat to this. The populations of Russia and the Ukraine have not experienced significant increases due to Russia’s invasion of the Ukraine. These countries are large agricultural producers and are well connected to other major agricultural producers. And they have the money to purchase goods. This is not true for people in most other conflict zones.

The real way to improve global food security is to reduce the number of wars/conflicts or facilitate reliable food supply into conflicts.

Conflict causes global food price volatility

Global price volatility is a direct outcome from conflict in large food producing countries. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine created significant volatility in global grain and fertiliser prices. So, while the invasion did not make Ukrainians hungry, it created hunger elsewhere.

The green revolution has not found its way to Africa

Climate change has caused localised food shortages in Africa. In wealthy and middle-income countries, food shortages can be made up through imports. This becomes harder in poorer countries for a number of reasons such as currency volatility, lack of transport infrastructure, lack of refrigeration.

The bigger picture problem is that the global agricultural revolution that feeds the rest of the world has left Africa behind. The continent has not seen yield growth anything like the rest of the world. The technology like irrigation, synthetic fertilisers, seed varieties already exists. It needs to find its way to Africa which will be the centre of global population growth over the next three decades.