China’s quest for food security is making inroads...except for pig feed

China is producing plenty of grains and meat. But Chinese pigs continue to face food supply chain vulnerability.

Almost all pieces on China’s agriculture start with how China's relentless food import growth has led it to become the world's largest agricultural importer. That is true, and the Communist Party of China has long seen it as a vulnerability.

However, in the last two years, the tide of China’s food imports have begun to turn. China has slowly reduced the value of its agricultural imports, including from the US. China's domestic agricultural production continues to grow as it has for the past 40 years, albeit at a rate slower than the rest of the world. China has also shored up domestic fertiliser supply and is now increasing domestic yields with less fertiliser.

The exception remains soybeans, but even on this front China has shifted its reliance from the US to Brazil. This is an improvement from Beijing’s perspective.

Image copied from this Reuters article: https://www.reuters.com/markets/commodities/china-pivot-us-farm-imports-bolsters-it-against-trade-war-risks-2024-11-01/

The small turn - a hopeful inflection point from China’s perspective - has been a decade in the making.

Food security is a serious business in Xi Jinping’s China. Xi has regularly talked about food security since he took office in 2013 and basically hasn’t stopped. As a report from CSIS notes, from 2012 to 2022, “Xi Jinping engaged directly on food security topics 67 times, including through domestic province inspections and instructions to local governors on how to manage agricultural production.”

There are two broad planks to the strategy. The first is boosting dometic research, yields and production to ensure maximum domestic supply (to be covered in another blog).

The second plank is shaping the international environment to secure China’s food security. No country is completely self-sufficient. Even large net food exporters, like Australia, rely on equipment, fertilisers, seed varieties, IP and a whole bunch of other international inputs. For China, which is the world’s largest food importer, complete self-sufficiency is not possible.

Xi Jinping’s output on this, as with many other topics, is prolific. But in a 2020 speech at the Central Rural Work Conference, he outlined the key international elements to China’s food security strategy. It has four specific commitments to strengthen supply chain resilience:

Diversification of agricultural imports (so if one country stop supplying, there are others)

Substitutability of agricultural products (so if there is a shortage in one product, there is a plan for others)

Improved ability to control key (global) logistics nodes

Support Chinese agricultural enterprises to go global (presumably to help secure a level of control over production in other countries)

Diversification and Substitutability: It’s a story of pig feed.

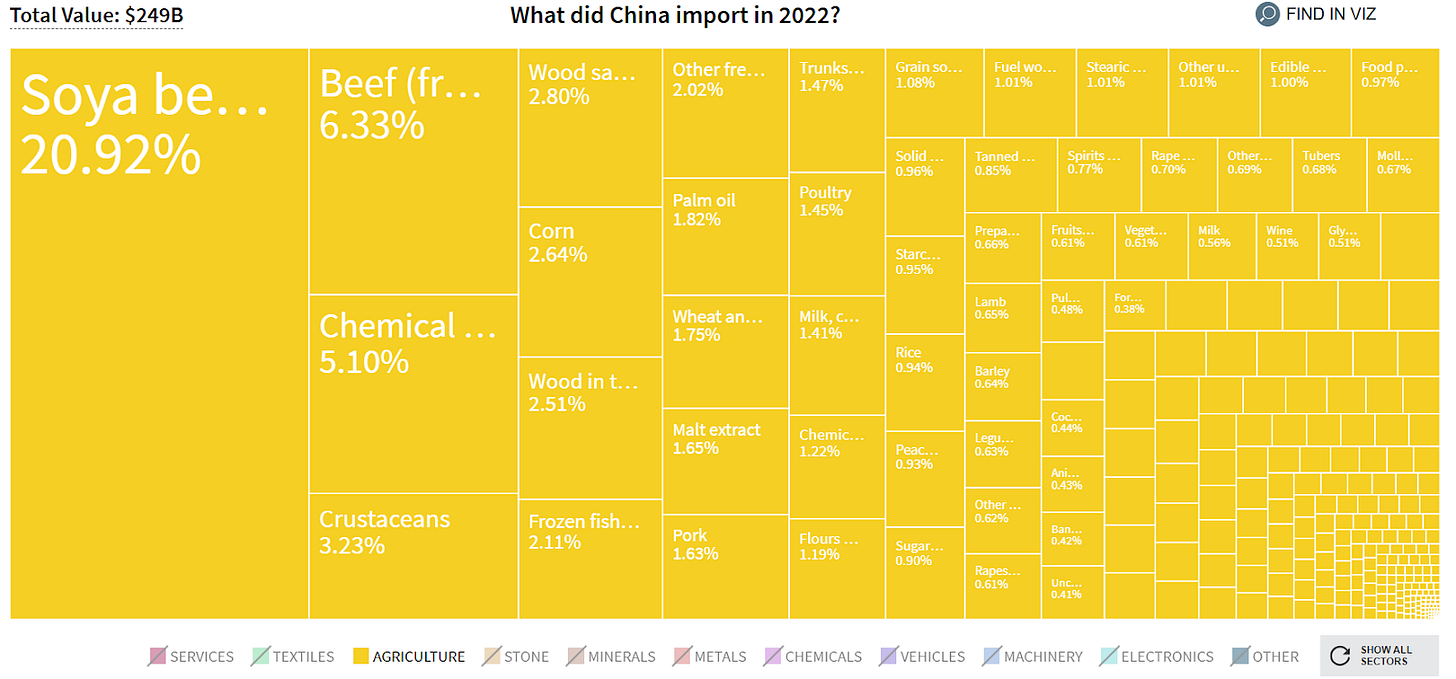

China’s biggest agricultural import - by some margin - is soybeans to feed pigs (visual below). China has half the world’s pig population. So it’s actually Chinese pigs that have a reliance on US imports.

Figure: China’s agricultural imports in 2022

This figure is a screenshot from the Atlas of Economic Complexity: https://atlas.hks.harvard.edu/explore/treemap?exporter=group-1&importer=country-156

Soybean substitution in theory is rather simple. Pigs are highly inefficient feed convertors. If PRC residents were to replace meat with vegetarian options, the soybean problem greatly improves. You’ll notice the second biggest import is frozen beef. Same solution.

But, people like eating meat. So, we have two scenarios. In wartime or other periods of unusual disruption, the population will accept meat rations and hardship for an extended period.

This is not likely to be acceptable in peacetime. So we see a diversification of soybean imports away from the US toward Brazil. This was initially driven by Chinese tariffs on US soybean in response to Trump's original tariffs. General diversification away from US agriculture has become clearer policy in China too.

Figure: China’s soybean imports becoming more reliant on Brazil (original here)

The longer term goal is not just to move reliance from the US to Brazil, but to reduce overall reliance on imported soybeans. China is trialling a bunch of solutions right now. One is to reduce the amount of soybeans in pig feed. The second is to grow more of its own soybeans.

So far it has not worked. China imported a record volume of soybeans in 2024. There are mitigating circumstances. Low prices and the looming threat of Trump 2.0 caused Chinese buyers to move soybean purchases forward.

The huge Chinese market has encouraged Brazilian soybean growers to expand. So for the next few years, weather permitting, we will likely see huge volumes of cheap soybean which may undermine China’s domestic soybean efforts as purchasers find international prices too attractive.

China is producing plenty of meat and grains

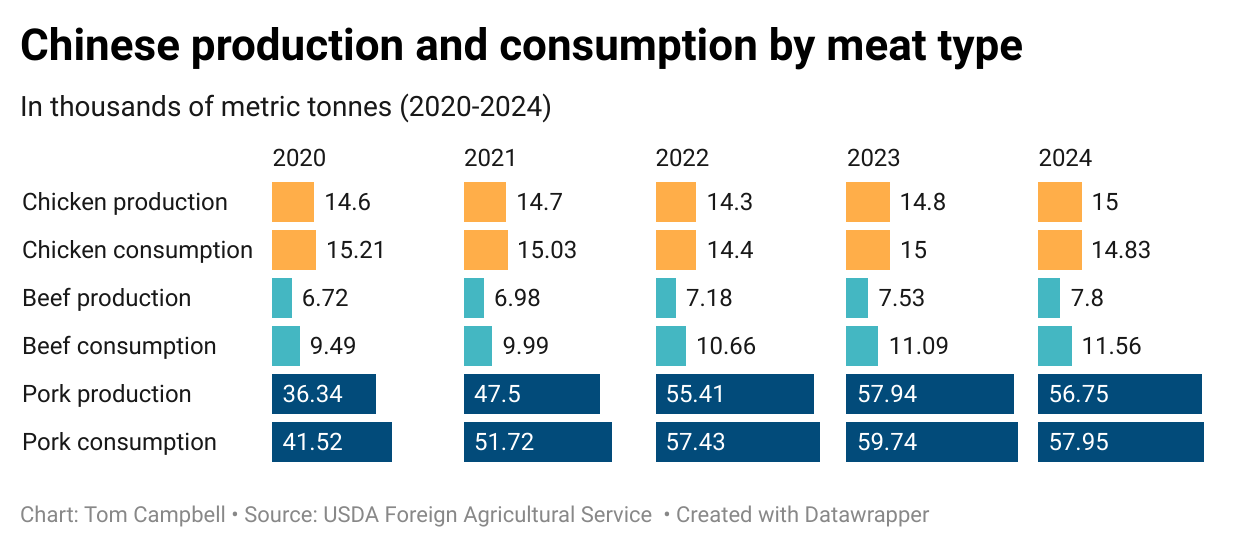

China imports meat and grains, but overall it has a high level of self sufficiency in these products. As the graphs below show, China’s domestic production of chicken and pork closely match its consumption. Similarly China produces enough beef to meef 70% of consumption. And it produces most of its own wheat and coarse grains.

And as you can see, China’s pork production has increased quickly. Feeding these animals remains the major vulnerability. But China is self sufficient in these key agricultural areas.

China’s diversification and self-sufficiency efforts will affect global growers in a multitude of ways

Grain crops like soybeans are commodities, so often if one market is unavailable then global supply shifts and the commodities get redistributed among other purchasers. A good example of this is Australian barley which found markets elsewhere when China blocked its purchase.

The exception is when one purchaser is larger than the rest. China consumes 60% of the world's soybeans. If supply shifts away from one supplier (in this case the US), then it encourages other producers (like Brazil) to boost their output which drops global prices. There is no easy solution for US farmers other than take the hit or find a new crop.

In most other grains, China is not the dominant purchaser to the same level. Beijing is trying hard to remove reliance on key US allies (like Australia), for example New Russia-China Land Grain Corridor (NLGC) program is designed to funnel Russian grains to China. They may well succeed. But grain producers in this case will find other markets in place of China.

Other agricultural goods like meat and crustaceans are awkwardly wedged between commodity and consumer goods. Some consumers have genuine preferences for meat from certain locations or suppliers. Others treat meat like a commodity. So countries like Australia and the US will continue to find niches that certain consumers like. But if supply from any of the major global meat or seafood producers is disrupted, China does have ready-made alternatives. And China will consistently try to find alternatives to major Western suppliers.

For value-added non-commodity products, it may be harder to replace the China market because it needs a large number of middle class consumers. There are few markets like that. Australia lobsters and wine makers, for example, struggled to find alternate markets when China lashed sanctions on Australia.

Thank you for an informative piece.