Biomanufacturing under Trump

BioMADE and congressional work continues, but scientific funding and previous presidential plans have been obliterated

Tom Campbell and Dirk van der Kley

Key Takeaways:

BioMADE has pushed ahead with 2 announced facilities with more in the pipelines. But China has recently announced a push for 20 facilities (we will do a comparison when there is actual steel going into the ground).

The President has dismantled key pillars of the Biden-era manufacturing plans - with little signs of a replacement.

US research on biomanufacturing will be reduced due to government cuts (just as China is ramping up).

There remains a lot of biotech interest among US politicians outside the executive branch.

Major powers plow money to prepare for the bio-revolution

Industrial biotechnology (the replacement of chemical processes with biological ones in modern industry) is a big deal. An oft-cited Boston Consulting Group report estimates that biomanufacturing will displace some 40% of the global economy over the next 30 years.

In practice, this future is still far away. The simple truth is that the cost for most-biobased products cannot yet compete with incumbents in chemicals, agrotech, fuels and food. We have seen this transition before with other emerging technologies, such as solar panels and wind turbines in the 2000s and electric vehicles and batteries in the 2010s. However, the scope of available bioproducts means that biomanufacturing will disrupt a much wider section of the global economy.

Countries are positioning themselves to be major producers (or developers) of biomass feedstocks and biobased products. The EU, China, Japan, India and South Korea all have well resourced plans to eventually lead in this sector. The US under Biden developed a cohesive bioeconomy strategy with the following elements:

Establishment of a new whole-of-government National Biotechnology and Biomanufacturing Initiative (NBBI)

Expansion of biomanufacturing capacity through coordinated government funding programs

Plans to build a resilient biomass supply chain to capture the feedstock competitive advantage

Usage of federal procurement as a lever to drive consumer demand for biobased products

Direct international engagement to grow the bioeconomy and increase biomanufacturing capacity globally with trading partners

In the near term under Trump parts of this strategy will continue, others parts have been rescinded, and others are in limbo. And then there is the destruction of the US’ underlying scientific and government infrastructure that will seriously undermine competitiveness in the long term. While the private sector and philanthropists are making up some of the void (see the American Alliance for Biomanufacturing) but cannot make up the total shortfall. Overall, the US is less likely to secure a lead in the global bioeconomy.

Win: BioMADE announces first facilities in its national network (announcements are a long way short of completed facilities)

The biggest challenge in the global bioeconomy is transitioning from lab scale to commercial at a competitive price point. There is a lack of affordable scale up facilities globally but it is particularly acute in the US where a lot of the fundamental research occurs. As a result, American companies, and in-particular early-stage ones, are left to use overseas manufacturing capacity for scaling-up.

One part of the solution to this is BioMADE, a Manufacturing Innovation Institute in the Manufacturing USA network. BioMADE has received significant federal support; following initial funding from the DoD of US$87 million in 2020, they have been supplemented with an increase of US$450 million in 2023.

This funding is expected to contribute to BioMADE’s ambition to establish a network of 12-15 pilot-scale facilities financed via public-private partnerships (thereby absorbing some of the economic risk private investors face).

BioMADE recently announced plans to refashion a facility in Maple Grove, Minnesota as the first facility in their network. This is an investment of at least US$132 million.

A few days later, BioMADE followed up with the announcement that they had reached an agreement with Lygos to ‘transition its pilot scale biomanufacturing infrastructure into a nationally available, multi-user facility’ operated independently by BioMADE. This represents an outlay of around US$80 million and becomes a second node in the network.

CEO of BioMADE, Douglas Friedman, thinks that this will be critical to changing the current status quo - “if a company can access a pilot facility six months earlier than before, that’s six months of wages saved. That might be the difference between survival and failure.”

This is an important first piece in the puzzle, but the picture is far from complete. As MIT researchers recently opined, BioMADE’s efforts alone won’t be sufficient to overcome the capacity issues in the country. In their words; “Simply building more facilities and capacity cannot match the pace of innovation and formation of hundreds of new companies annually”.

In their view, more focus is needed on the process engineering to deal with the complexity of biologically derived products. This complication means that building more capacity will not always equate to more productivity, due to adjustments made to downstream processing or growth time for each bioproduct. Standardisation of biomanufacturing processes is a necessary step (and the biopharmaceutical space provides a blueprint for this e.g. monoclonal antibodies, mRNA vaccines). Decreased operational costs using automated and modular technology will also help to reduce the barrier for start-ups to scale up. However, at present both of these technologies are still in their adolescence.

Douglas Friedman has hinted that there will be another facility announced this year; remaining locations from BioMADE’s shortlist of sites includes Georgia, Hawaii, Indiana, Iowa, and North Carolina. While getting steel in the ground is important (and certainly is a sign of good progress), the critical step for BioMADE is whether they are able to secure funds to contribute to the second wave of facilities and beyond. Whether their network ambition is accomplished or not depends on whether the Trump administration has any policy platform for biomanufacturing, and whether the DoD is seeing a payoff from funding.

Win: BioMADE membership growth continues to be strong

Additionally, BioMADE progressed their second ambition of establishing a nationwide biomanufacturing ecosystem. Their efforts over their first 4 years of operation have fostered the growth of this network, underlined by an announcement in March that they had surpassed 300 members. In a recent podcast appearance, Douglas Friedman noted that they had reached 325 members.

Why is this a good sign for the bioeconomy in the US?

The majority of members are in industry but aren’t just startups looking for more funding opportunities - indeed, major players like Cargill, Amryis, and Ginkgo Bioworks are equally involved. BioMADE has brought together these companies with lab spin-outs via funded projects that are mutually beneficial to both. I expect that these connections would not have occurred to the same extent without BioMADE, and this sharing of skills and expertise is valuable for both innovation and upskilling of the current bio workforce.

Additionally, there are non-negligible numbers of universities, community colleges and non-profit members who are contributing to biomanufacturing education. This is also important; an increase in funding for workforce development projects will help address existing deficits in access to appropriate training for biomanufacturing jobs (see pg. 21 of this report).

Win (with a wait and see caveat): The establishment of a bipartisan BIOtech caucus

The caucus chairs are key supporters of the National Security Commission on Emerging Biotechnology. And it demonstrates a bipartisan resolve (alongside many state-level legislators) that the US should further prioritise this technology. It remains to be seen how effective they will be in overcoming some of the losses outlined below.

Loss: Trump revokes EO14081

Trump’s March wave of rescissions included Executive Order 14081, ‘Advancing Biotechnology and Biomanufacturing Innovation for a Sustainable, Safe, and Secure American Bioeconomy’. This order was a key part of Biden’s bioindustry policy, directing five federal agencies to collaborate on a concerted biomanufacturing strategy, the first national level policy since Obama’s National Bioeconomy Blueprint. This is a disappointing end to one of the most coordinated US industrial plans in recent history; the Biden-Harris administration previously claimed that government interest in the bioeconomy spurred investment of more than US$63 billion into the biomanufacturing sector.

As part of the fact sheet released alongside the rescissions EO14081 is accused of “funnell[ing] Federal resources into radical biotech and biomanufacturing initiatives under the guise of environmental policy”. This is a bold critique, and not language that inspires confidence for future government investment.

Moreover, the timing of this rescission entails that a number of directives are left in limbo. According to a dashboard compiled by the Federation of American Scientists, almost half of the mandates of EO14081 are yet to be delivered on. This means that a number projects will presumably be left incomplete, including:

A collaborative plan by USDA, EPA and FDA proposed an update to the Coordinated Framework for the Regulation of Biotechnology (last updated in 2017) by December 2024. This has not been published and is a major oversight given the advent of Alphafold2 and other biological design tools that have expedited biotechnology research.

A plan from the Department of State with regards to science diplomacy, including best practice for participation in the global bioeconomy. On a similar topic, an interagency report on national security risks from foreign adversaries against the bioeconomy and from foreign adversary development has not been published.

A range of goals relating to the development of a biobased procurement system remain unmet. Such a framework would have provided a clear route for market entry. With Trump favouring petrochemicals it is unlikely that we will see much needed subsidies on biobased products.

Given Trump’s rhetoric on fossil fuels, this move is perhaps unsurprising, but the critical truth is that without a new strategy or directive, the US will squander an opportunity to become a major player in the global bioeconomy. Other global powers can and will seize on this gap in the market; China, Japan, and the EU have all been making moves to build their biomanufacturing capacity.

Loss: A deepening trade war with China will present challenges for the whole biomanufacturing pipeline

In the first months of Trump’s second administration, the US levied 145% tariffs on Chinese imports. Beijing then retaliated with tariffs on US imports as high as 125%. As the trade war between the two nations continues, consumers everywhere are facing higher prices and uncertain supply.

Science and industrial biotech are not immune to this - and it will affect all levels of the biomanufacturing pipeline, from fundamental science to construction of facilities. The US is the largest importer of lab reagents globally, and laboratories are already citing increased quotes for glassware and basic reagents (that are largely from China), and high-end analytical equipment (from Japan and Germany).

This is placing further strains on labs, who are now facing the reality that the National Science Foundation (NSF) will cap overhead payments in new grants at 15% . This will require a major adjustment by universities - who already lose an estimated US$6.8 billion in indirect costs. If these economic pressures persist, something will have to give, and fields with less of an immediate impact such as microbial engineering could be on the chopping block.

The good news for the US in the competition sense is that the effect is flowing both ways - Science recently reported that Massahusetss-based nonprofit Addgene had to cancel a contract with Peking University academic Tang Fuchou for plasmid delivery, citing tariffs. Major imports of high-end instruments and speciality research materials are at risk, and could leave Chinese labs without antibodies, restriction enzymes, stem-cell materials and tissue culture products. A disruption is significant - in 2024 alone China imported US$12.5 billion worth of precision instruments from the US. While the 2021-2025 national science plan stated a goal of establishing emergency reserves for critical research supplies, I expect that this buffer is not enough to be self-sufficient yet.

However, a trade-war could have worse effects than just increased input costs. There is a major risk to scientific progress, and as each country is the other’s biggest research partner by a considerable margin, prohibitions on collaboration would invite intense geopolitical competition over scientific research that we haven’t seen since the Cold War.

Loss: Funding for DBIMP and NSF has been gutted

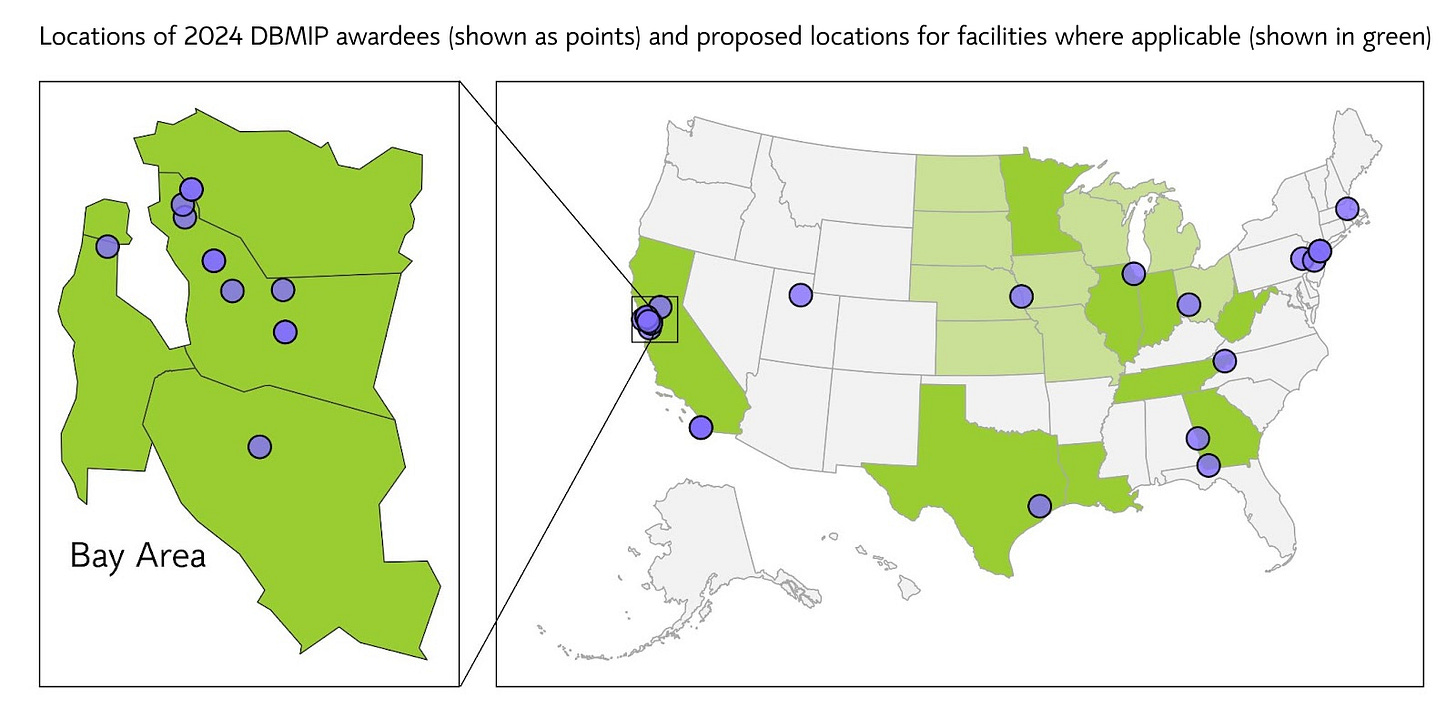

In addition to backing BioMADE, the Department of Defense has a separate funding stream for projects that bolster US supply chain security of biomanufactured goods via the Distributed Bioindustrial Manufacturing Investment Program (DBMIP), initiated in 2024. Individual awards in this program are typically in the range of US$1.5-3 million, which goes towards producing business and technical proposals that can then receive follow-on awards of up to US$100 million to construct facilities. During the first year of operation, 34 awards were given out.

The FY25 President’s Budget requested $125 million for the biomanufacturing of critical chemicals. However, as of December 2024 neither the House nor Senate appropriations bills made mention of DBMIP. Consequently, the program is at risk of being hollowed out before it has the opportunity to achieve anything beyond facility feasibility studies. While this is useful, if it doesn’t put steel in the ground then the impact will be pretty small.

The recently published National Security Commission on Emerging Biotechnology (NSCEB) has noted the consequence of this, and recommends funding of at least US$762 million across the next five years for DBMIP. This would be vital to building domestic biocapacity - if the US is serious about biomanufacturing as a strategic issue, they can’t afford to hesitate in providing multi-year funding for these programs.

But it isn’t just biocapacity that is at risk. Trump has also taken the sword to the National Science Foundation (NSF), with research grant funding at its lowest level in nearly 30 years. According to recent analysis by The New York Times, grant funding for biology is at 50% of the previous 10-year average. From a geopolitical perspective, this will undermine the US’ bid to retain their competitive advantage in innovation and thereby diminish their competitiveness with China in the global biomanufacturing market.

Win: National Security Commission on Emerging Biotechnology issues its report and recommendations to Congress

In 2022, Congress tasked the National Security Commission on Emerging Biotechnology (NSCEB) to develop recommendations to advance US leadership in biotechnology. Last month, the commission presented their final report and a list of recommendations to Congress.

The primary recommendation is clear: the US government should invest at least US$15 billion over the next five years to ensure the growth of the US biotechnology sector.

The publication of a report is a pretty small win - the tangible impact depends on whether the subsequent National Biotechnology Initiative Act (H.R.2756, S.1387) gets support in the House and the Senate. In the current political climate this is a big uncertainty. The NSCEB will exist for another 18 months before dissolving - for the ambitions of the Act to come to fruition, they need to make their voices heard. This could go a long way to making biomanufacturing a bipartisan policy and provide much needed coordination and oversight.